Information management in timber buildings

To search all text on this page

On Windows – Press Ctl+F

On Mac – Command+F

This site is suitable for a wide range of users, with technical information

levels 1 and 2 available on closed toggles

Technical level 1 Technical level 2

The importance of information

- Different data types

The UK’s Building Safety Act

- The ‘golden thread’ principles

- The ten points of the ‘golden thread’

Quality control and workmanship

- Auditing processes

The average building, from inception to use, generates many Gigabytes of information – from design specifications, costings and drawings to post-occupancy evaluation and in-use costs. The data comes in many forms, graphical and non-graphical, documents and planning process data and models.

Different data types (Technical level 1)

A non-exhaustive list might include :

- Client brief and technical requirements

- Appointments and contracts

- Bonds and insurances (including final building insurance valuation)

- Project stage reports

- Technical reports (planning, design, environmental, impact assessments, etc.)

- Analysis, assessments and calculations

- Sustainability certification – assessment, application, certificate

- Surveys (topographical survey, condition survey, etc.)

- Meeting minutes

- Project file notes

- Requests for information (RFI’s)

- Method statements

- Correspondence

- Media (photographs, images, presentations, video, etc.)

- Regulatory application/submission certificates (planning, building control, fire safety, disability access)

- Non-statutory applications/submissions/certificates (LEED, BREEAM, etc.)

- Tendering procedures (pre-qualification, Requests for Tender, Submissions, Assessments)

- Models (3D models, 2D models, federated models, analytical models)

- Design drawings, specifications, schedules and data sheets

- Cost plans and bills of quantities

- Payment certificates

- Contracts final accounts

- Project plans and programmes

- Technical submittals and approvals

- Construction/fabrication drawings, specifications, schedules and data sheets

- As-built drawings, specifications, schedules and data sheets

- Health and safety risk assessments and safety plans

- Design responsibility matrix

- Design requirements (tests, certificates, samples, etc.)

- Compliance specifications/certificates/opinions on compliance

- Schedules of certifiers, benchmarks, design changes, non-compliance

- Inspection plans and inspection records

- Snag lists and quality control procedures

- Systems, equipment, materials and products:

- Product specification

- Agrément certificates (NSAI, BRE, etc)

- European Technical Assessments (ETA)

- Product Declaration of Performance (DoP) and CE Marking

- Environmental Product Declaration (EPD)

- Technical data

- Product batch/trace details

- Product installation guide

- Product maintenance/cleaning procedures/manuals

- Product spare parts, tools and resources

- Product safety information/emergency procedures

- Inspection record

- Test certificates

- Commissioning certificate

- Equipment default “settings” (set points)

- Suppliers warranty (parts)

- Suppliers warranty (labour)

- Supplier contact details

All construction projects have complex supply chains. It is common to have 50-70 specialist contractors and sub-contractors, including cladding and timber specialist suppliers, manufacturers and installers. Most projects involve a large number of low value transactions. In many types of built projects 25% of the subcontracting arrangements are of values below £10,000 (BIS study, 2013).

As a consequence, information requirements and the volume of exchanges are vast, interactions complex and building processes vary and need to adjust to circumstances. Construction activities inevitably have interactive complexities and tight coupling among systems, i.e. a high degree of interdependence. Information and data collected are often fragmented, incomplete and inaccessible.

The statistics for information capture in construction are patchy, yet key for the owner to efficiently and effectively manage a building, in operation as well as in maintenance and refurbishment.

Anecdotal evidence suggests a high percentage of projects have no complete documentation, be it on ‘as-built/as designed’ information or mandatory health and safety files (a mandatory requirement since 1994). Many investigations confirm that it is unclear whether the information shared with owners at completion of a project reflects design intent, as constructed, or as completed status of a built asset.

Failure to record and report key information can have far-reaching and potentially catastrophic consequences. The tragic fire at Grenfell has shown the perils of poor accountability, particularly in relation to specification and potential changes to design or construction activities.

The Building Safety Act was granted Royal Assent in April 2022, becoming an act of parliament and enforced as law. It delivers far-reaching reforms, giving residents and homeowners greater rights, powers and protections. The building safety act specifically addresses the importance of appropriate information collection and transfer.

The practical implementation of the Act is the responsibility of The Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). To support its implementation, secondary legislation is in the process of being drafted under the Building Safety Act 2022. This is not expected to be published before 2024.

The Act creates three new bodies (the Building Safety Regulator, the National Construction Products Regulator and the New Homes Ombudsman scheme) to provide oversight of all buildings, with a special focus on high-rise buildings.

Following recommendations from Dame Judith Hackitt, the Building Safety Act has introduced requirements for key information to be recorded and submitted in a formal record for the design, construction and occupation phases.

For each stage it requires:

- Assigned responsibility (to Dutyholder/Accountable Person/Building Safety Managers) for managing the potential risks and what is required to move to the next stage.

- Creating and maintaining a ‘golden thread’ of vital information about the building to be gathered over its lifetime and held digitally.

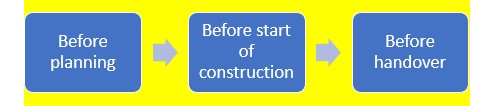

The ‘golden thread’ information is submitted by Dutyholder/Accountable person and/or Building Safety Manager at key stages during the build process:

Figure 1: The Golden Thread

The ‘golden thread’ is to ensure that that the ‘the right people have information to support compliance with all applicable building regulations at the right time’.

The ‘golden thread’ principles

The golden thread principles for key information management requirements have been outlined by the Building Regulations Advisory Committee as:

- Accurate and trusted

- Residents feeling secure in their homes

- Culture change

- Single source of truth

- Secure

- Accountable

- Understandable/consistent

- Simple to access

- Longevity, durability and shareability of data

- Relevant and proportionate

The ten points of the ‘golden thread’ (Technical level 1)

- Accurate and Trusted: the Dutyholder/Accountable Person/Building Safety Manager and other relevant persons (e.g. contractors) must be able to use the ‘golden thread’ to maintain and manage building safety and ensure compliance with building regulations. The Regulator should also be able to use this information as part of their work to assess compliance with building regulations, the safety of the building, the operator’s safety case report, including supportive evidence, and to hold people to account. The ‘golden thread’ will be a source of evidence to show how building safety risks are understood and how they are being managed on an ongoing basis. The ‘golden thread’ must be accurate and trusted so that relevant people use it. The information produced will therefore have to be accurate, structured, and verified, requiring a clear change control process that sets out how and when information is updated and who should update and check the information.

- Residents feeling secure in their homes: residents will be provided with information from the ‘golden thread’ so that they have accurate and trusted information about their home. This will also support residents in holding Accountable Persons and Building Safety Managers to account for building safety. A properly maintained ‘golden thread’ should support Accountable Persons in assuring residents that their building is being managed safely.

- Culture change: the ‘golden thread’ will support culture change within the industry, as it will require increased competence and capability, different working practices, updated processes and a focus on information management and control. The ‘golden thread’ should be considered an enabler for better and more collaborative working.

- Single source of truth: the ‘golden thread’ will bring all information together in a single place, meaning there is always a ‘single source of truth’. It will record changes (i.e. updates, additions or deletions to information, data, documents and plans), including the reason for change, evaluation of change, date of change, and the decision-making process. This will reduce the duplication of information (email updates and multiple documents) and help drive improved accountability, responsibility and a new working culture. Persons responsible for a building are encouraged to use common data environments to ensure there is controlled access to a single source of truth.

- Secure: the ‘golden thread’ must be secure, with sufficient protocols in place to protect personal information and with controlled access to maintain the security of the building and residents. It should also comply with current GDPR legislation where required.

- Accountable: the ’golden thread’ will record changes (i.e. updates, additions or deletions to information, data, documents and plans), when these changes were made, and by whom. This will help drive improved accountability. The new regime is setting out clear duties for Dutyholders and Accountable Persons for maintaining the ‘golden thread’ information to meet the required standards. Therefore, there is accountability at every level – from the Client/Accountable Person to those designing, building or maintaining a building.

- Understandable/consistent: the ‘golden thread’ needs to support the user in their task of managing building safety and compliance with building regulations. The information must be clear, understandable and focused on the needs of the user. It should be presented in a way that can be understood, and used by, users. To support this, Dutyholders/Accountable Persons should, where possible, make sure the ‘golden thread’ uses standard methods, processes and consistent terminology so that those working with multiple buildings can more easily understand and use the information consistently and effectively.

- Simple to access (accessible): as the ‘golden thread’ needs to support the user in their task of managing building safety, the right information must be accessible at the right time. This means that the information needs to be stored in a structured way (like a library) so people can easily find, update and extract the right information. To support this, the government will set out guidance on how people can apply digital standards to ensure their ‘golden thread’ meets these principles.

- Longevity/durability and shareability of information: the ‘golden thread’ information needs to be formatted in a way that can be easily handed over and maintained over the entire lifetime of a building. In practical terms, this is likely to mean that it needs to align with the rules around open data and the principles of interoperability. Information should be able to be shared and accessed by contractors who use different software, and if the building is sold the information must be accessible to the new owner. This does not mean everything about a building and its history needs to be kept, as the ‘golden thread’ must be reviewed to ensure that the information within it is still relevant and useful.

- Relevant/proportionate: preserving the ‘golden thread’ does not mean everything about a building and its history needs to be kept and updated from inception to disposal. The objective ‘ is building safety and therefore information that is no longer relevant to building safety does not need to be kept. The ‘golden thread’, the changes to it and processes related to it must be reviewed periodically to ensure that the information it contains remains relevant and useful.

Information requirements

Many publications are available to give generic advice on the implementation of the ‘golden thread’ for buildings. A summary of key information to be considered is shown below:

| General | Timber specific |

| Specification: Construction products, materials, components, information, including key performance characteristics, including fire | Generic, key design features ensuring the performance of timber construction, such as sole-plate details, moisture management, differential movement provisions, fire performance features, treatments, durability provisions. |

| Plans: How to manage performance, fire and other issues |

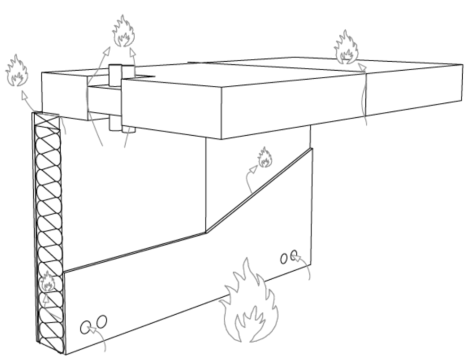

Maintenance requirements, quality and workmanship expectations. The performance of a product or fire-separating element can be severely undermined by poor installation. In the event of a fire, poorly installed or maintained components can lead to spread of the fire and compromise fire safety provisions. For example, any significant gaps in the line of a cavity barrier can lead to fire spreading through the cavity, circumventing compartmentation provisions. Key fire safety information and considerations in timber buildings.

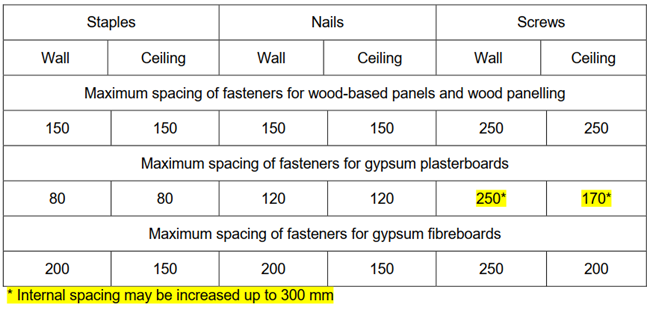

Joints between assemblies must be tight to prevent flames and hot gases penetrating through the construction during the required fire resistance period. It is therefore essential that any joints and gaps are filled with a suitable product that is fire-rated for the required fire resistance period. Fire protective panels

Gaps in panels that are backed by timber and are greater than 5 mm are considered to increase the charring rate of the timber members, so any gaps greater than 5 mm should be reported to the designer for reassessment of the fire protection. Where multiple panel layers are used to form the fire-resisting element, the joints between adjacent panels should be staggered by at least 60 mm in order to avoid a continuous joint being created, and each panel should be fixed individually to a structurally competent material. Insulation Junctions between elements Penetrations and openings

|

| Models: Building as planned | Generic |

| Fire statement: Fire service access, fire fighting water accessibility | This is generally applicable, see Fire-fighting access and facilities for further information. |

| Construction control plan: How compliance is achieved and changes controlled | Generically applicable. Timber supply-chain partners should be identifiable and their guidance on how to maintain and inspect timber components available for access. |

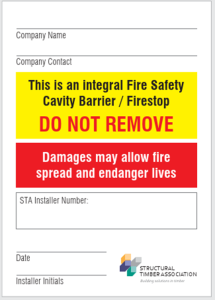

Quality control processes at each trade interface are vital to underpinning the fire safety strategy of any building. Contractors and installers must have sufficient and continuous training to understand the requirements for achieving the fire safety features of their work and follow an audit and checking process during the installation and modification of any fire critical elements of construction.

Auditing processes (Technical level 1)

Example of an audited label identifying a fire critical element in the building construction

Example of digital timber specification platform being developed by Swedish Wood

BIM offers many opportunities to deliver the ‘golden thread’ with a robust and efficient platform for collating information on fire and other key performance features.